Come Back to Me

by Sejal Shah

Author's Note: My book launch was many things, but not a wedding do-over. I began this companion essay in late 2019 and handed in the final version to the editors at Texas Review in February 2020. I see it now as a time capsule of what life was like pre-pandemic. My virtual book launch for my debut essay collection, This Is One Way to Dance, was earlier this month, hosted by Brookline Booksmith. Over 200 people attended, but I was in my study alone, with my husband helping me with tech issues. We pulled the clip of a modern dance piece by Garth Fagan Dance, with which we had planned to end the evening, because of the social media blackout and to recognize and mourn the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor—to say Black Lives Matters.

We are in a different world now. This Friday, June 26th, 2020 is my fifth wedding anniversary. I have to tell myself: keep moving. There are no do-overs. Write the next book.

Come Back to Me

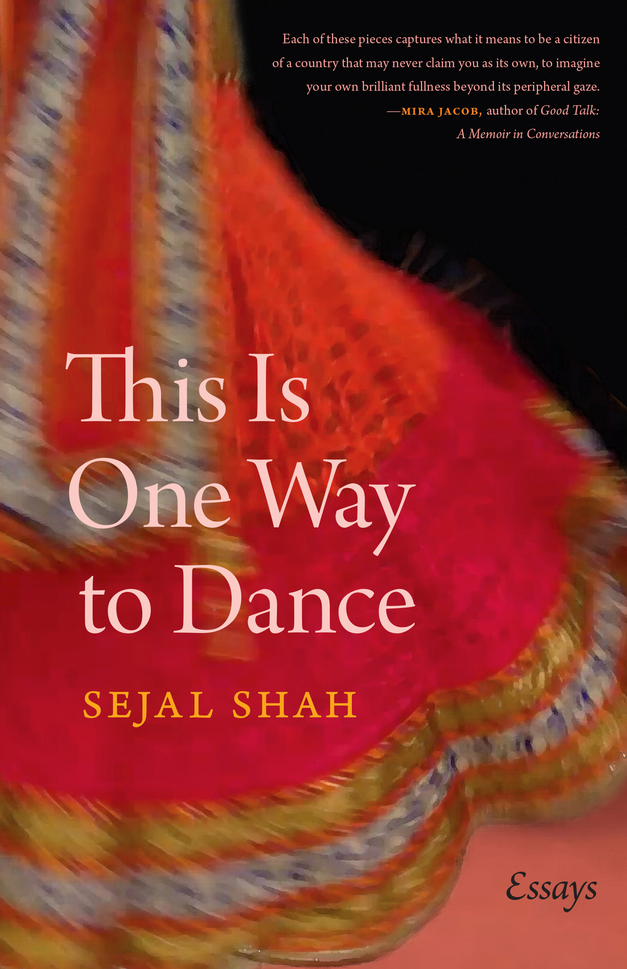

I wanted a book more than I wanted to get married. And I cared about this book more than I cared about any details of my wedding. I could imagine the cover of my essay collection more than I could ever conceive of a sari or a theme. The red dress that got away, come back to me, chuniya chori, returning. The flaring, the turning, motion, spin. The declarative sentence—This Is One Way to Dance—instead of my first title, Things People Say.

I wanted accessibility and readability. I wanted space, calm, for the typeface to breathe. I'm not thirty. I wanted to be able to read from my book at readings without fussing with readers, adjusting for distance when I looked up from page to audience as I do.

Five years ago, in June, I married another teacher from my hometown. One of the best parts of our wedding was the dinner for close out-of-town friends after the ceremony. It was in the barn in the back of the independent school where we met. Our friends speaking, Missy playing the violin; Michael reading a poem; Max, a former student, deejaying 80s songs for us. Alessandra told the story about the time Bill Clinton walked by us at work with Secret Service officers trailing him, how he nodded, said, "Hello, ladies," and despite ourselves, we giggled, caught off guard by his famous charisma and smile.

On June 2nd, my book arrived, launched.

I've been waiting for this day as long as I can remember. Not my wedding day or the day I had my first kid (we are not parents)—but the publication of my first book, twenty years after I wrote the first piece in it. It's taken me time—longer than most of my classmates. I was later than most of them to get married, too.

The cover of your book is your dress, and the cover of mine is an image of the chuniya chori—a Gujarati outfit meant for dancing, for garba and raas—which I didn’t buy and wish I did. It fit perfectly, it was heavy with embroidered handiwork, it cost twice as much as the one I bought.

I bought a different one, spring-like, cotton candy pink and mint green, lovely and less money. I bought it one weekend in New Jersey, on a street of Indian stores, nearly six hours away from where we live. We had only one day to shop—we couldn't be away from my grandmother for longer than that. I chose wrong. The blouse ended up needing too much alteration: the sleeves had to be detached in order for me to lift my arms. My skirt's drawstring snapped minutes before our first dance. The aunties safety-pinned the skirt to my tights. They zipped up my blouse, forced bangles onto my wrists, warned me not to drink anything—(safety pins held me all together). I wish I had bought the other dress.

My book: the typeface, leading, ornament—are my theme, flowers, wedding favors.

This Is One Way to Dance is a memoir in essays. Several essays began as stories; several are lyric essays. Editors Deborah Tall and John D’Agata defined the form in the Seneca Review, which is based close by in the Finger Lakes region of western/central New York: “The lyric essay often accretes by fragments . . . its import visible only when one stands back and sees it whole . . . it elucidates through the dance of its own delving.”

A book is a kind of dancing, a series of steps, structures, questions, echoes, answers.

I cringed drafting the apologetic emails, the awkward blurb requests. These testimonials helped form the structure, the scaffolding I needed, what I missed in my own wedding. I didn’t have bridesmaids. It was a Hindu ceremony, very traditional, nearly three hours long. I did need some backup, friends in uniform to stand up there with me and my synopsis and author bio—someone else’s words to read. Book blurbs are toasts—attendants, your mentor and other writers’ kind words shoring you up, illuminating the text around you.

I wrote my own introduction. I wanted someone wise and older (Fairy godmother? A famous writer or spokesperson or editor or critic?) to anoint me, but it fell on me to walk myself down the aisle, albeit escorted by feedback from editors and friends. I felt, and they did, too, that my book needed some connective tissue, structure, a frame—a roadmap. How do I contextualize these essays? How do I make a frame around a mosaic of pieces? They are new and selected essays, words collected for twenty years to form my first book, essays knit together to form a memoir, to create a collage.

I wrote about genre—I swam through it—how I began as a poet, survived an MFA in fiction, then began to write more nonfiction. Essays gave me both the most freedom and resistance. I liked the tension, walking the line between genres. Having come up in a two-genre MFA (fiction or poetry? we’d ask upon meeting someone at those early parties), nonfiction was beyond—nonbinary, queer, expansive, wider. Thinking through these questions and finding the arc of the essays—the shaping, the questions they asked and answered, bookended by my brother’s wedding (opening) and mine (ending)— transformed a collection of snapshots into a kind of memory stitched from silence, speech, and essays. They became an album I wrote, arranged, recorded, and remixed over twenty years.

I think it’s fitting that the cover image of my book is the dress I didn't wear. Writing is like that—living life twice—trying to render and come to some resolution, grace, with loss, the passage of time. I would never want a second wedding—the first wedding was hard enough—finding a tailor to sew sari blouses that fit; managing spreadsheets, guest lists, table assignments, taking care of Ba, the matriarch of our family, whose stroke had overnight transformed her from head chef to being unable to walk or lift a spoon.

In June, we will have been married five years. Our parents suggested we marry soon after we met, that summer. Why wait, they said. Too soon, we said. They were right. Life doesn’t wait. That August, my friend Jim, my MFA classmate, became the first American journalist to be murdered by ISIS. We traveled to two memorial services. That fall, my aunt's cancer returned. She left Chicago and moved to Rochester, New York, to live in my parents’ house with them, my grandmother, and me. In December, near midnight, Ba opened her mouth to speak and she couldn’t; after her stroke, my uncle and aunt flew from California, staying for a month to help. I kept teaching ninth grade English, Romeo and Juliet. A wedding seemed like something to get through—we plowed forward and did what we could. I wouldn’t say we enjoyed anything leading up to it.

My grandmother cooking.

Photo courtesy of the author.

My book is a tiny bit of a do-over. I want to find more joy in ushering this book into the world than I did in being a bride. I wrote new essays, updated essays, revised others, completed others; a few short stories became essays, a few essays got cut, and it's now a memoir in essays across time.

It’s hard to let go. The United States isn’t the same in 2020 as it was in 1999. This Is One Way to Dance spans those years and more. I could rosary those words endlessly, I know, but I don’t want that—I want to let it go. I want to write new books. What do you do after a wedding? This book is our daughter. I wrote it and my husband managed production, proofing, and editing. What do you do when your kid goes off to college?

Putting a book out into the world is not like throwing a wedding—anyone can take the book out of the library or buy it—no limits to your guest list. But it was a little about wanting to have what my photographer friend Preston suggested—an annotated wedding book. Other people’s ideas of my wedding, particularly non-South Asians’ ideas aggravated me, nails on chalkboard: limited, exoticizing, colonialist, frustrating, maddening. You can’t relive your wedding, and I don't want to—but I can write books. This is my first.

Detail from our wedding reception. Photo credit: Preston Merchant.

I do still think about a different wedding. I'd wear the red-orange chuniya chori, the color of a flame, one that needed no alterations, one that fit. I'd block the obnoxious relatives and friends who angled and lied and pressured to get something or other (special seating, an invitation, a dance performance) for their daughters. I'd submit an announcement to the New York Times. I'd do the dessert tasting. (I told R it sounded stupid, but what was I thinking? I wasn’t. We like dessert.)

Marriage is a protected status in this culture and many others, but it doesn’t solve the problem of life. I had a good single life. I married after I had given up on the whole thing—I had met many kind, interesting people in my life and then I left New York City and moved home to my smaller city, where people marry younger, and I went on a few dates (complicated, kids, exes) and that was fine. I had enough friends who were married, or had been, to know it wasn’t a perfect solution to anything—not life, not unhappiness, not loss. I appreciated my life: I had time to write, I lived near (with, even) my family. Then I met this middle school teacher at work.

***

Much of what I love about weddings lives on in This Is One Way to Dance—the bright shock of colors, family, conflict, food, friendship—flourishes. And though it’s a book with a lot about weddings in it, it’s more about what we do when we’re not getting married or attending weddings, which is to remember to search out moments of joy and any occasion to dance.

We had a beautiful first dance to America’s “You Can Do Magic,” choreographed by our friend Natalie, a professional modern dancer, a longtime Rochesterian and Trinidadian American. For R and me, Bollywood would have been campy. She got that, she got us. I remembered listening to America in Sarah and Tina’s room next door to mine in college—they had the Greatest Hits CD—it brought back 1982 and MTV, being ten and wondering what my life would be like and would I ever find someone, and what would that look like. I never even thought about what I would wear.

Dance rehearsal video still from video taken by Natalie Rogers-Cropper at the Garth Fagan Dance Studio.

No, I lied: I did feel, after years of watching the afternoon soaps—Guiding Light, One Life to Live, All My Children—crestfallen, when I realized it would not be a cake-like cascading white frosting dress. I could not have imagined this red gold orange flare, this notion of a girl in motion, then grown, spinning and spinning and turning and turning herself.

I could not have imagined what it would feel like to hold my book, my bright, imagined cover: a bird, a shock of color, my name—myself, but not myself—something I made held in my hands.

Sejal Shah is the author of the debut essay collection, This Is One Way to Dance (University of Georgia Press, 2020). Her essays have appeared in Guernica, Literary Hub, Longreads, and The Rumpus, among others. The recipient of a 2018 NYFA fellowship in fiction, Sejal recently completed a story collection and is at work on a memoir about mental health and academia. She is on the faculty of the Rainier Writing Workshop low-residency MFA program at Pacific Lutheran University. She lives in Rochester, New York.